Exhibition Proposal

Double Negative

A rendering of trauma and transformation

An exhibition proposal by Lisa Kessler and S. Billie Mandle

Double Negative combines documentary and abstraction into a rendering of trauma and transformation. The work depicts the Catholic Church as neither a site of awe or contempt, but as a stage where the reckonings of today were foretold twenty years ago. Double Negative explores both the quiet and the active engagement necessary for structural change.

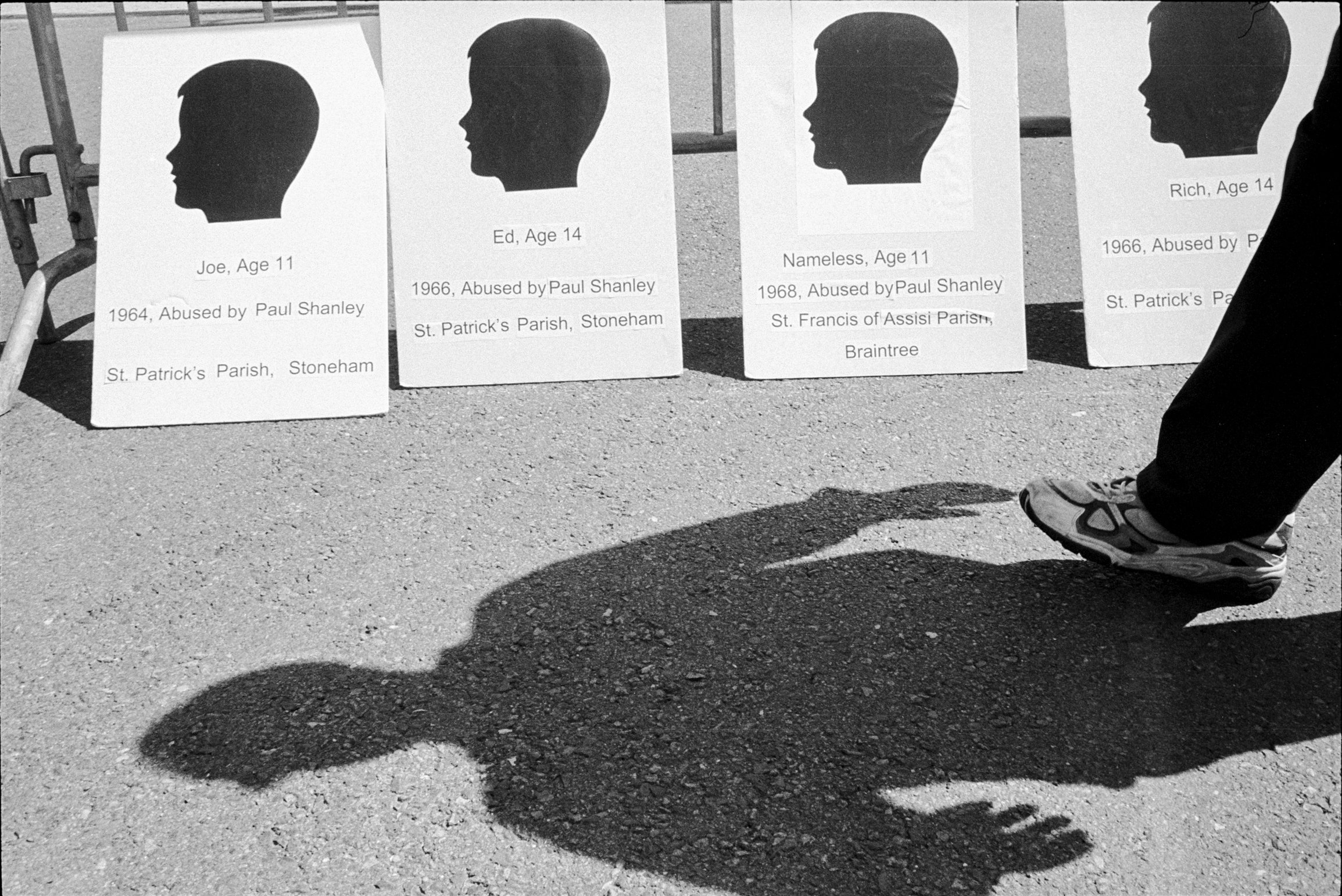

Clergy abuse victims forced Americans to reassess how they thought about sexual abuse, power, and the Catholic Church. Beginning in the early 2000’s in Boston, courageous victims —both men and women— spoke publicly for the first time of being raped and molested by priests. They soon discovered they were not alone as a cacophony of victim/survivors revealed a consistent narrative. Ultimately, the Church’s own documents validated victims’ accounts and exposed decades of complicity and knowledge. Many people whose families had deferred to the church’s denials now discovered the empathy and anger that had eluded them. They saw a system and a structure predicated on secrecy, denial, pay-off and cover-up of known predators.

Clergy abuse survivors’ confrontation of power, sexism and homophobia remains a foundational stepping-stone for the “Me Too” movement. What began in Boston is nothing short of the transformation of power structures everywhere: people who were silenced have been empowered to speak up across all sorts of institutions that shield perpetrators.

Lisa Kessler

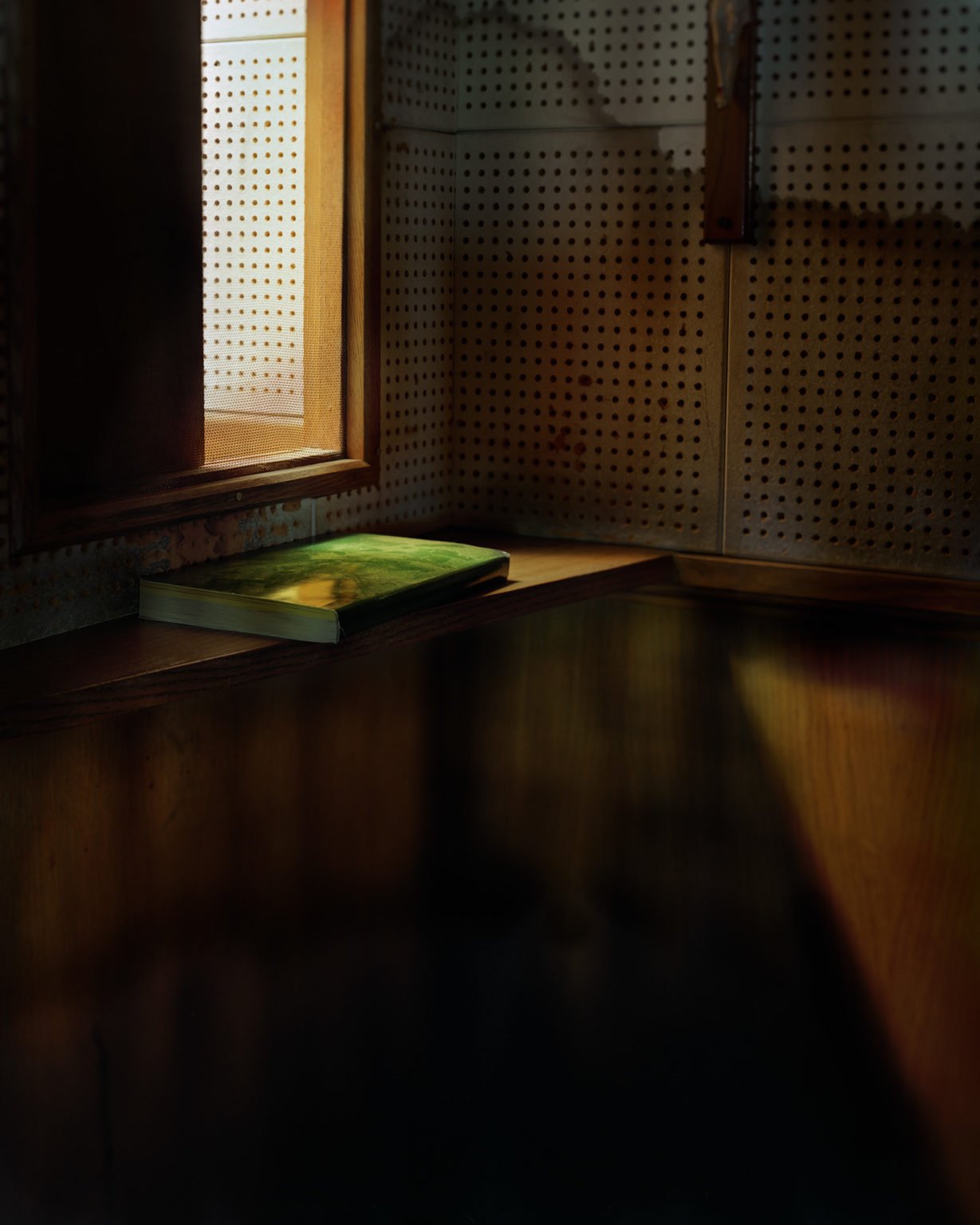

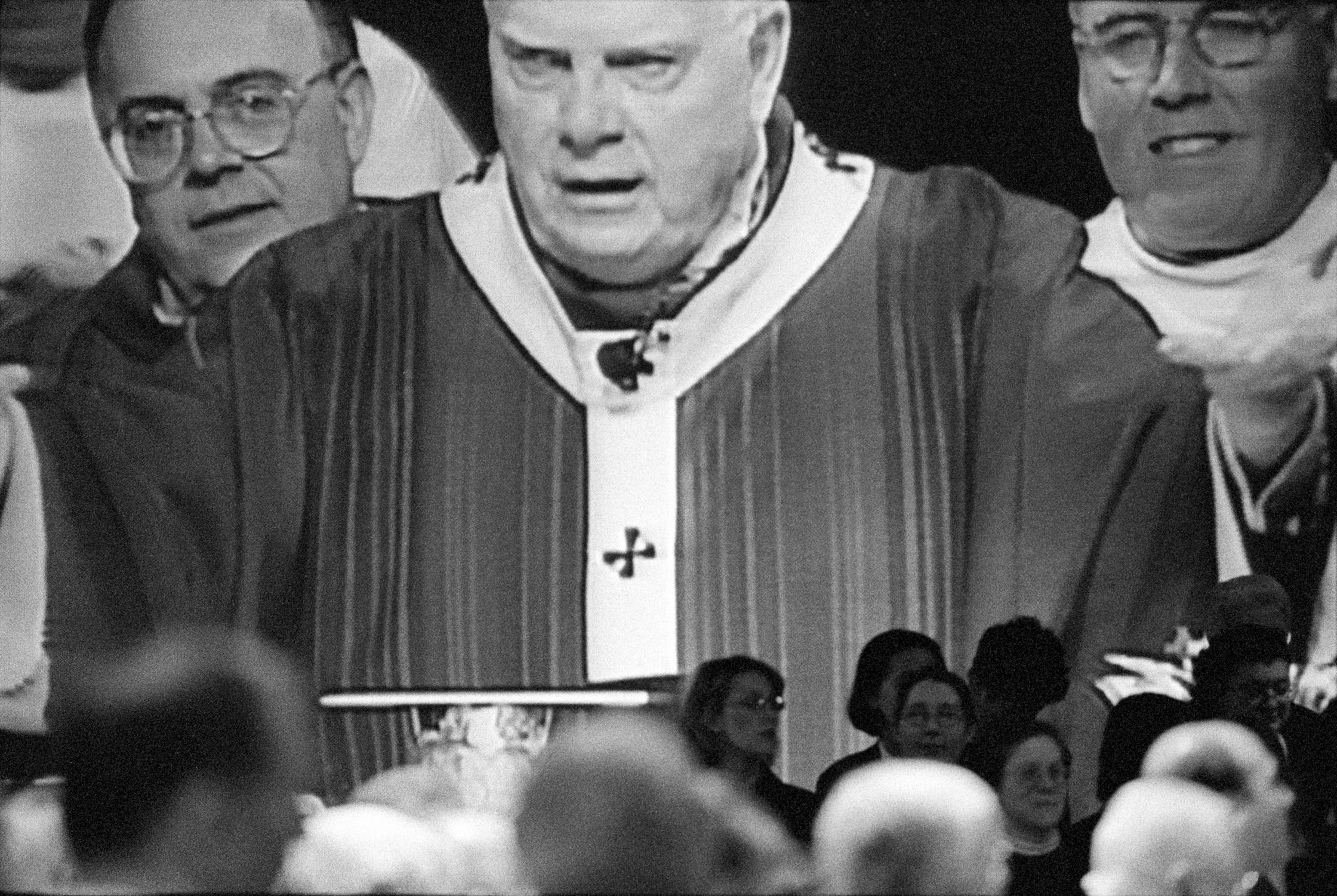

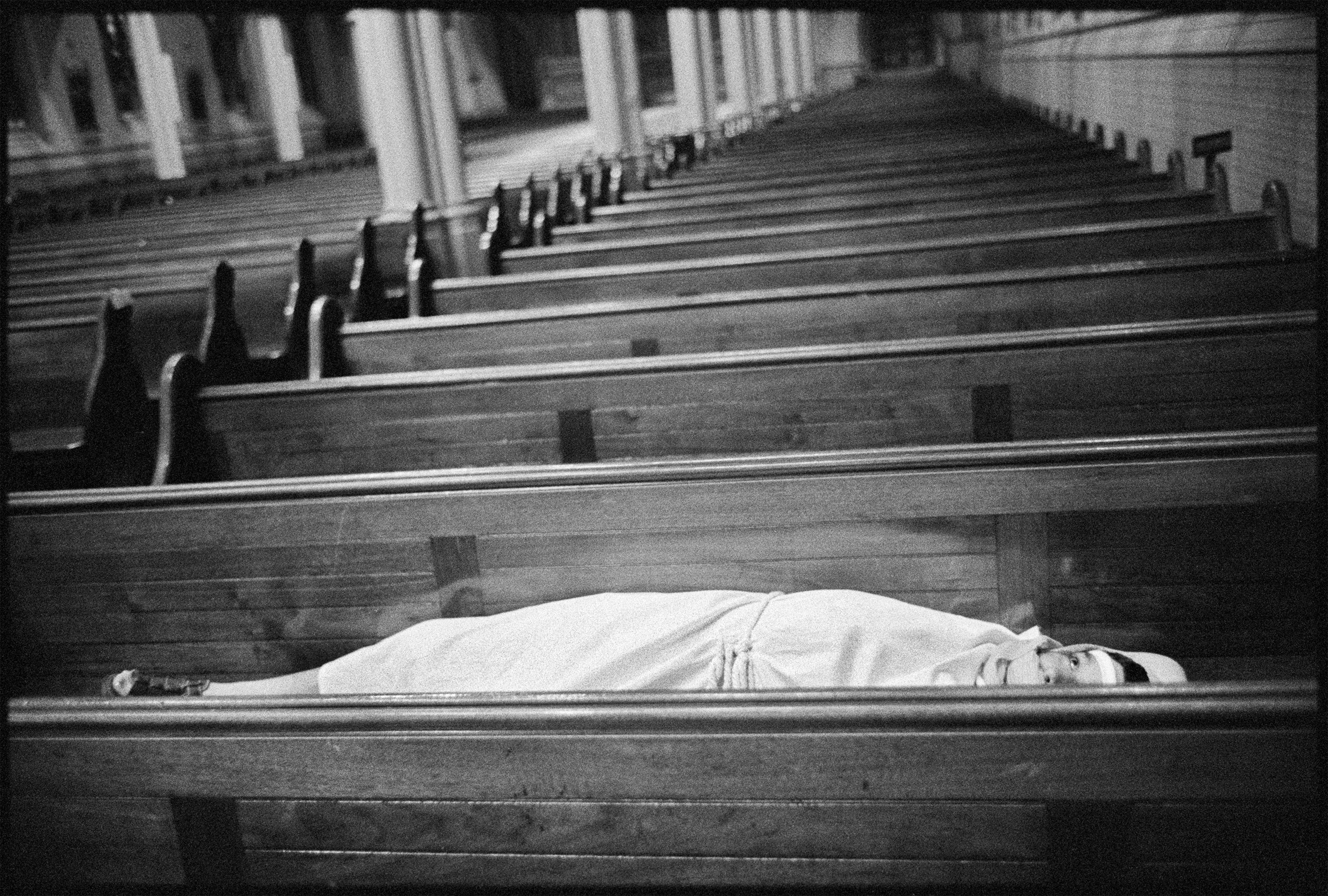

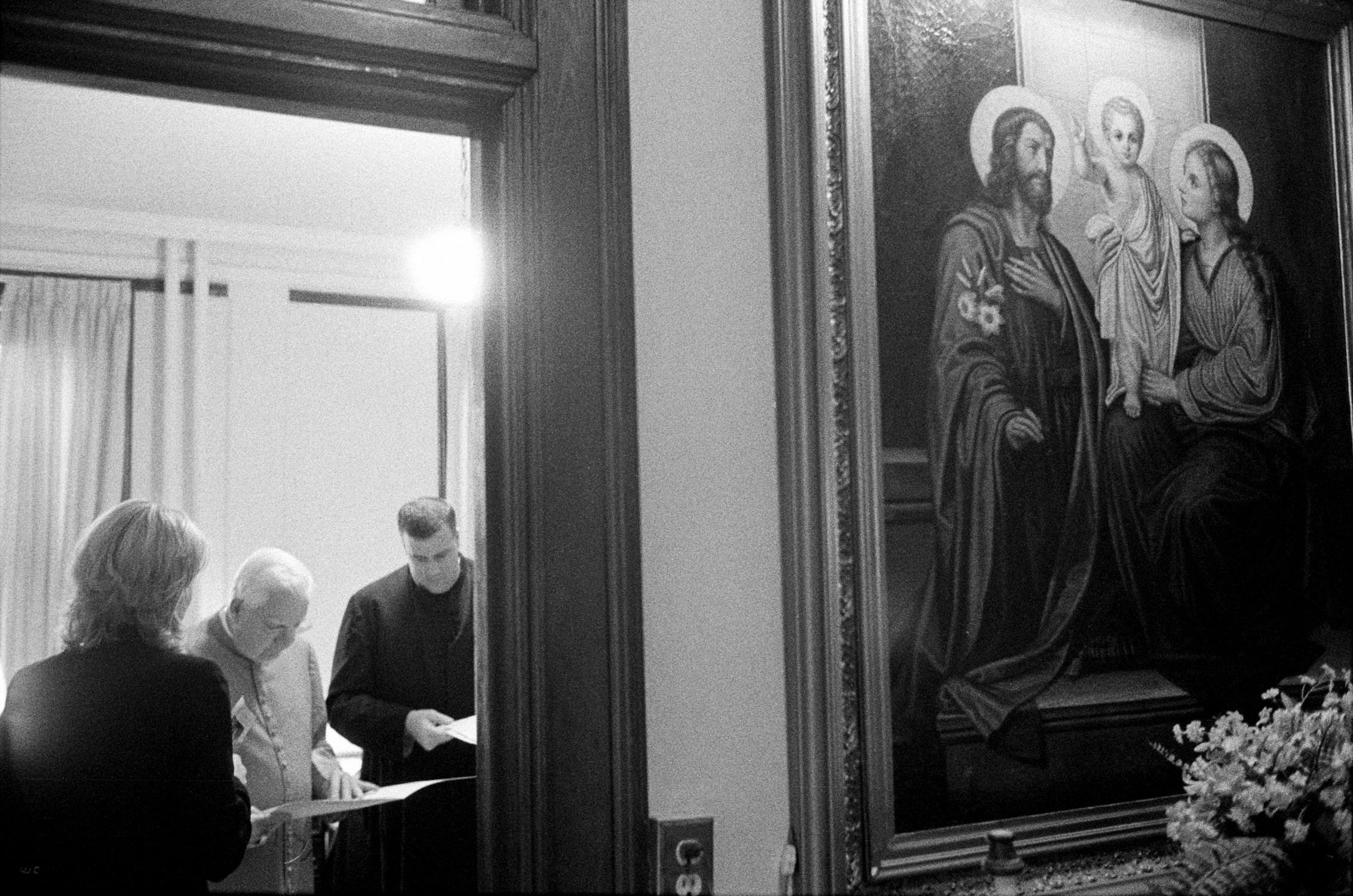

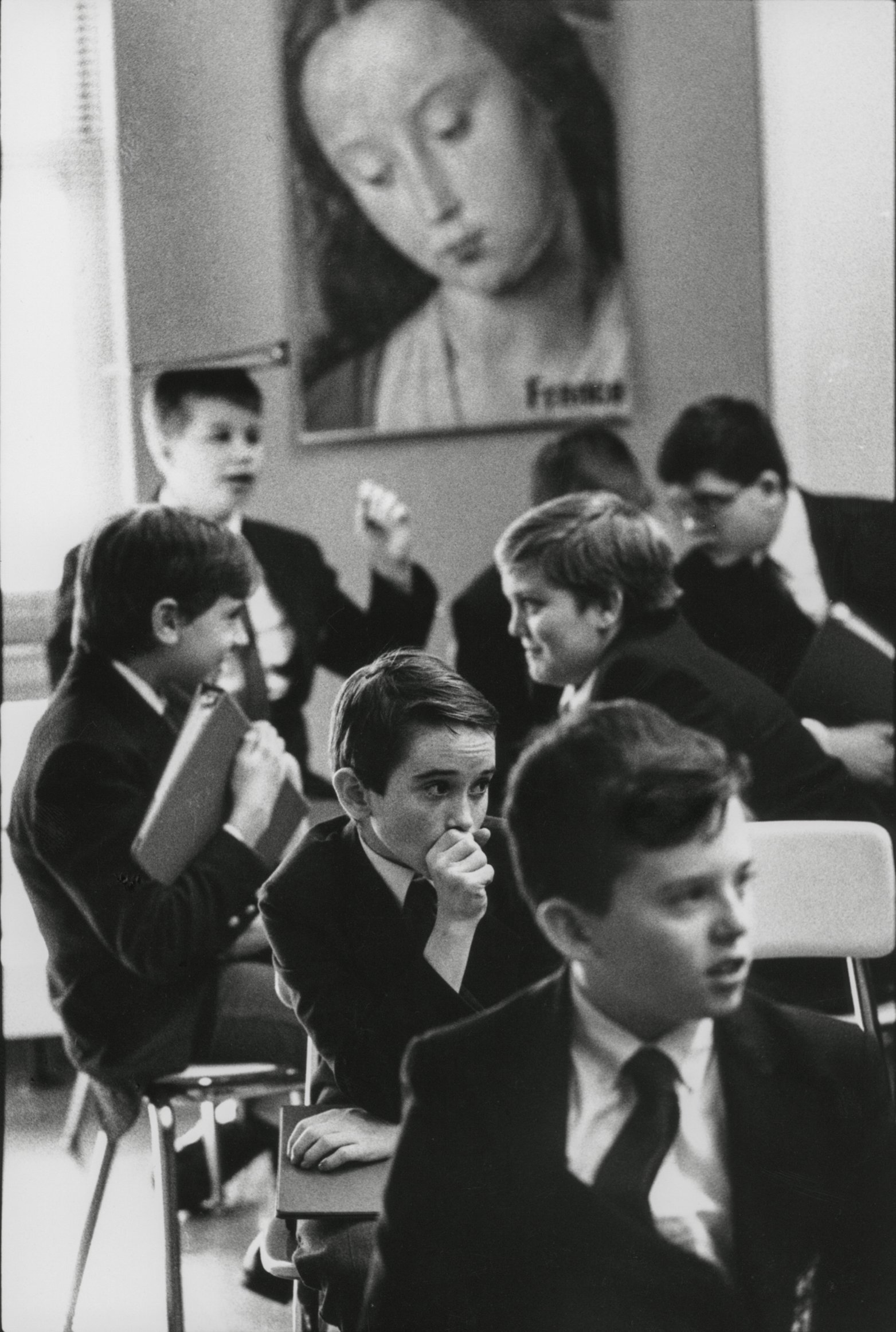

From 1990 to 2000 Lisa Kessler was a regular contributor to the archdiocesan newspaper, The Pilot. Over time, her role expanded as she became the photographer of record for the Boston archdiocese, documenting important events and the work and travels of church leaders, including Cardinal Bernard Law. Kessler, a secular Jew, was now an insider witness to the power structure, personalities and workings of the Catholic Church, in what was then the most Catholic of cities in the U.S. In 1999 she was awarded a Massachusetts Cultural Council Artist award for her personal project “Catholic Backstage,” later exhibited as “Shades of Grace.” That early work, typically made before and after assignments, captured both a sense of community and a feeling of profound isolation she witnessed in the church.

When the clergy abuse scandal erupted in 2002, Kessler returned to the church, this time as an outsider, to document the crisis as it unfolded. She met with protesters to discuss her role as an independent documentarian. She also requested access from Cardinal Law to document what was unfolding inside the church. While she hoped at first to witness a healing in the form of an acknowledgement by the church hierarchy, she soon saw that the failures of the institutional church were endemic to its structure.

Billie Mandle

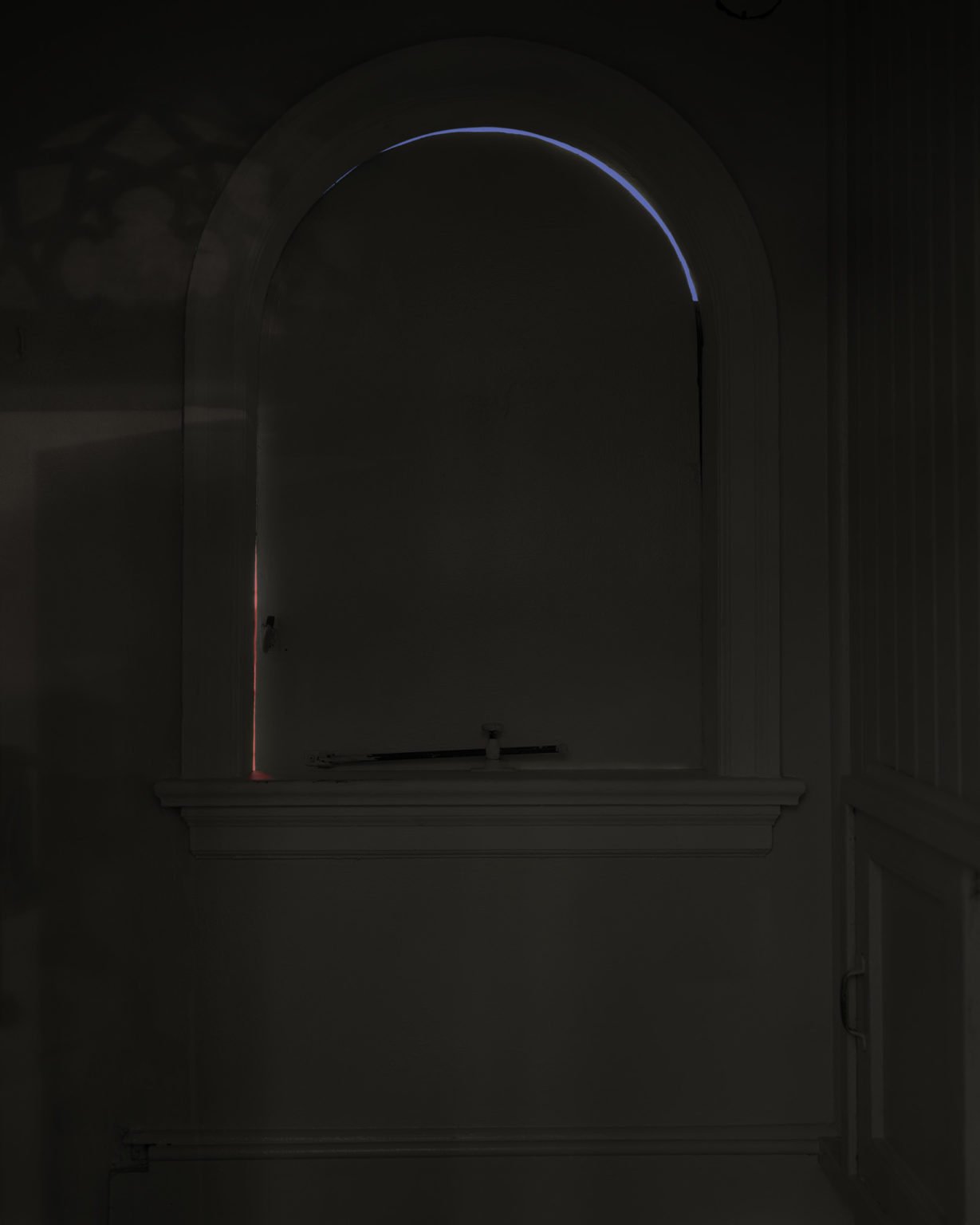

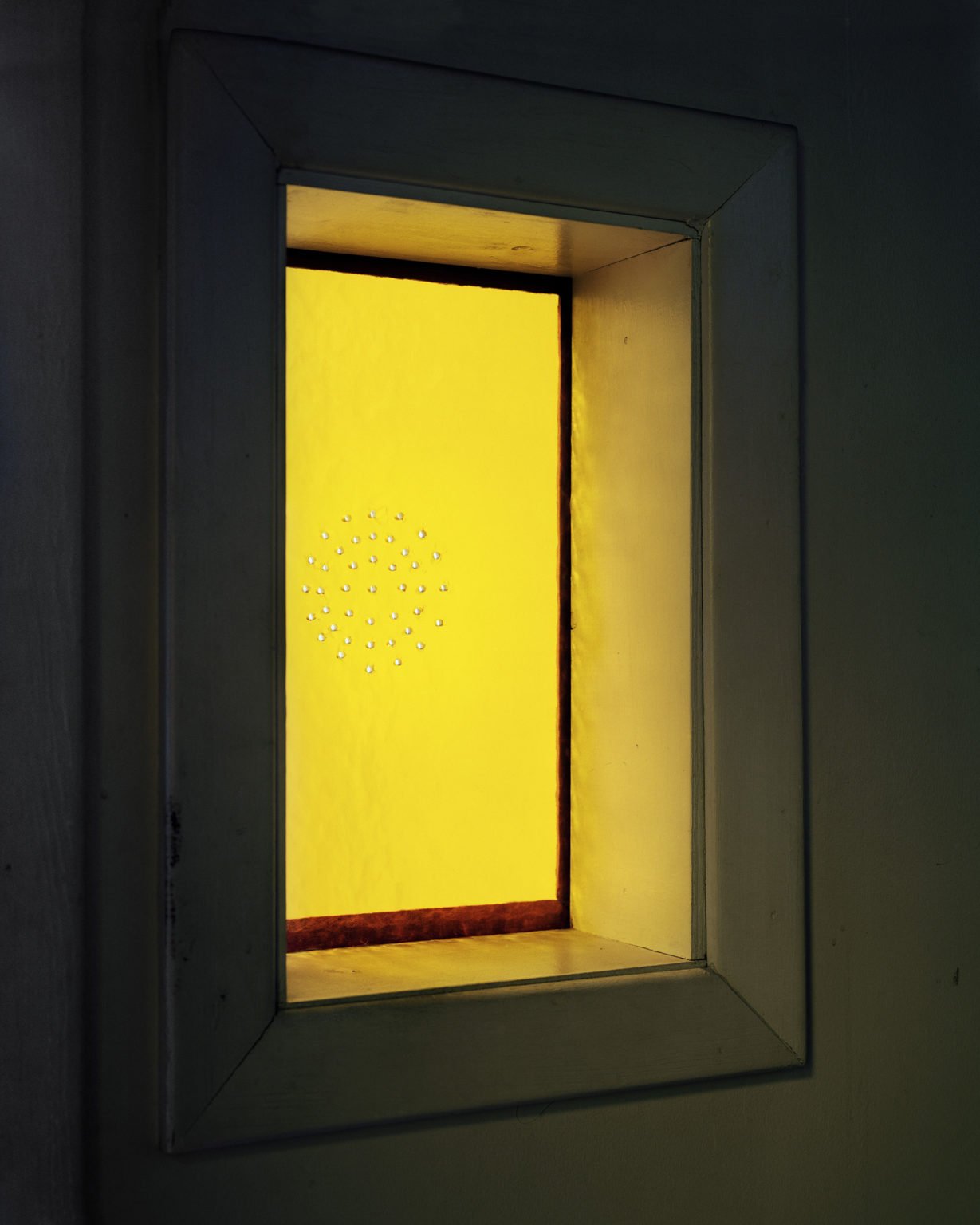

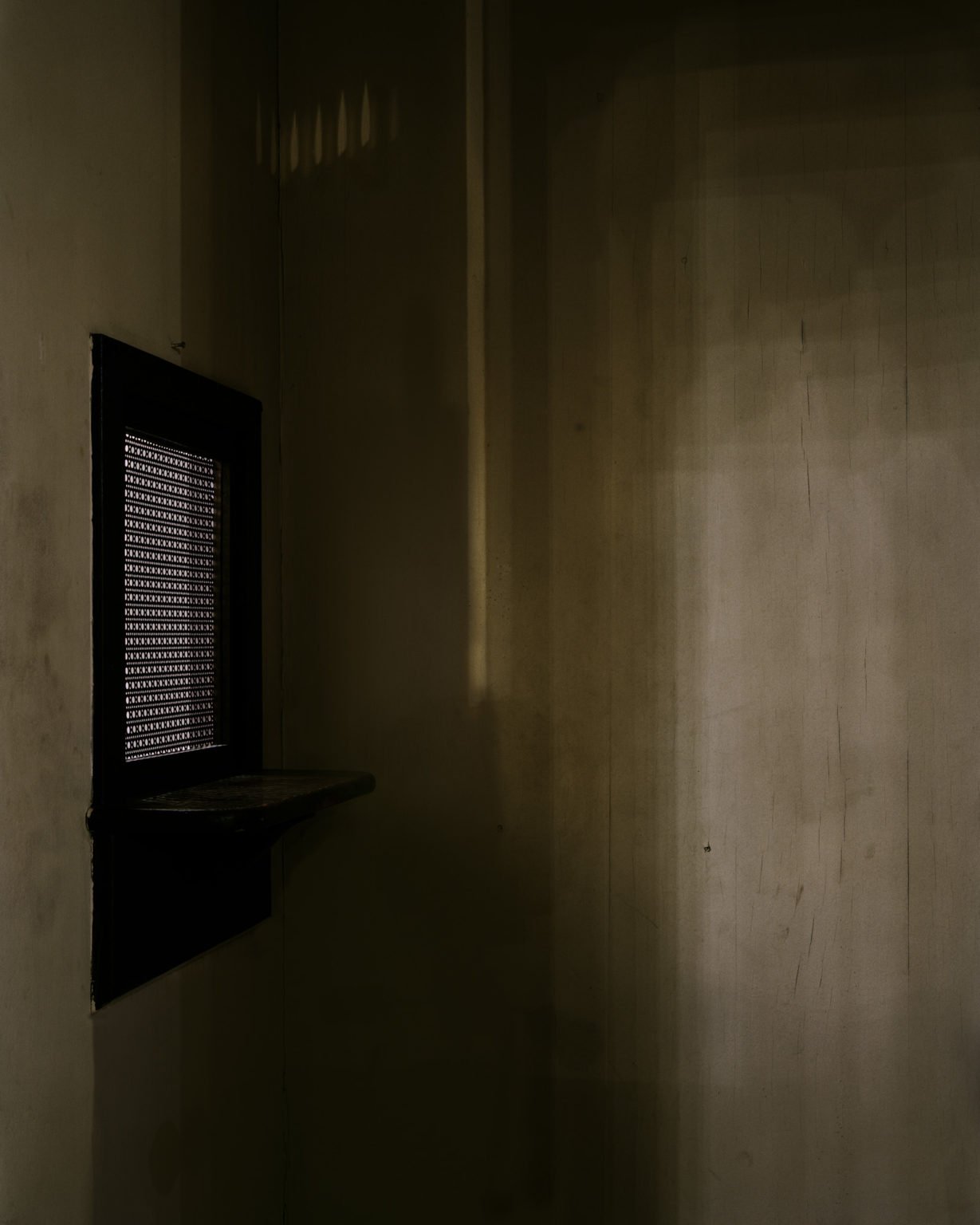

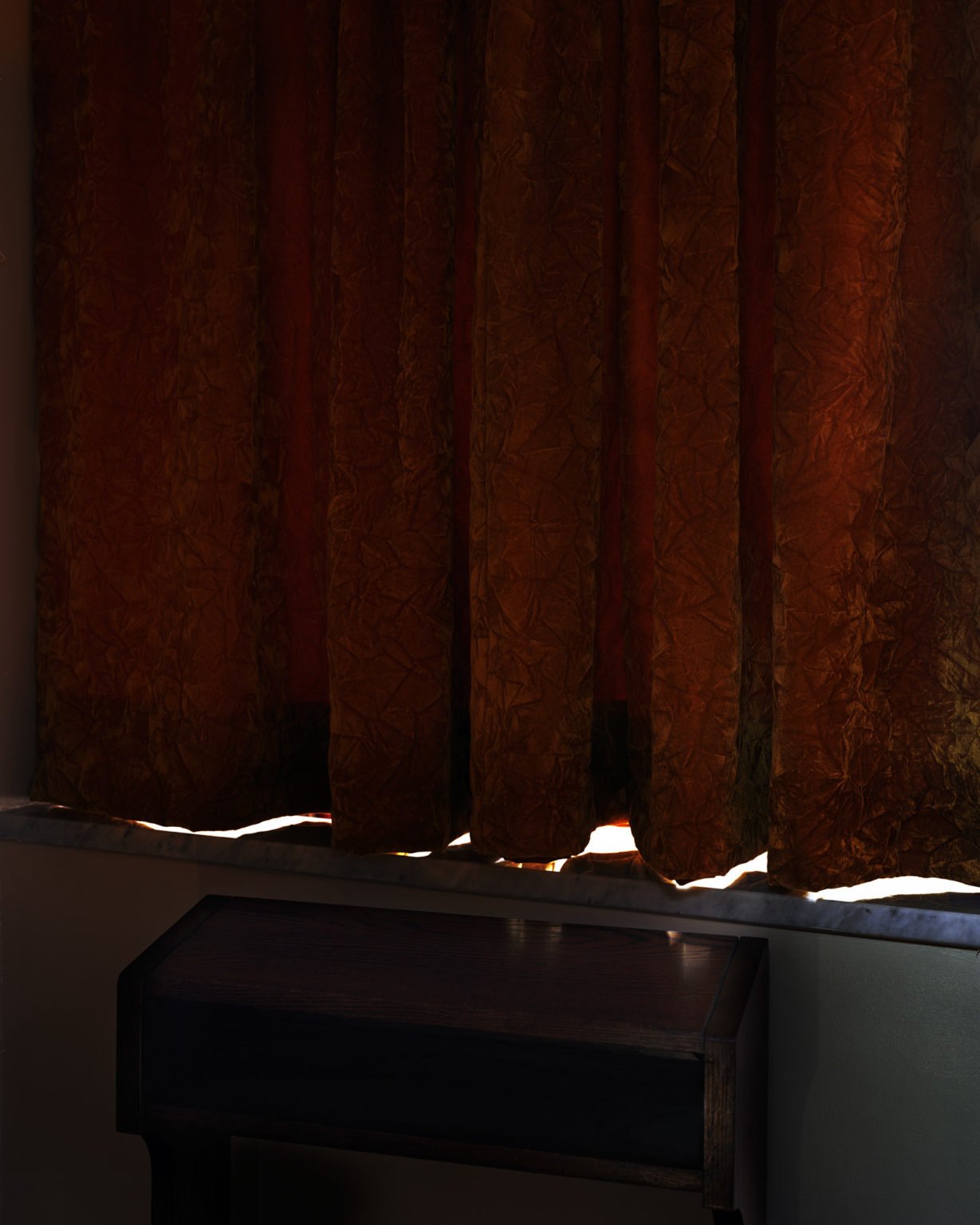

In 2007, Billie Mandle embarked on a ten-year journey through the United States photographing the dark interiors of confessionals in Catholic churches. Working slowly with a 4 x 5 view camera and available light, she made long exposures from the perspective of the penitent, creating color images that are more metaphorical than typological.

As a queer woman raised Catholic, Mandle’s photographs were an interior way of grappling with (her own) darkness. Confessionals hold traces of secrets and sins -- traces from each penitent, and traces from the Church. Each visitor seeks redemption surrounded by layers of past confessions. Her book “Reconciliation,” published in 2020 by Kehrer Verlag, transforms the confessionals from places of stark binaries — good/evil, light/dark, absolver/sinner — into sites that expose myriad, nuanced contradictions.

The pacing of Mandle’s photographs is slow and quiet; they provide an interior, intimate counterpoint to Kessler’s exterior, active photographs. Authentic change requires a reckoning with both the active work of facts, histories and politics, and the quiet work of reflection, feeling, and listening while acknowledging multiple layers of shame and guilt in one collective space. Double Negative posits such multiplicity as a path forward.

Double Negative

The title Double Negative has multiple connotations. It begins with two photographers who pointed their cameras at the Catholic Church and saw more than religion. It references photographing with negative film (Mandle in color, Kessler in B/W), as well as their outsider/insider and insider/outsider status (Kessler, a Jew with access to the inner sanctum of the church; Mandle, a Catholic who felt herself an outsider to the church).

Most powerfully, the grammatical meaning of Double Negative reflects the pervasive thinking of colluders distancing themselves from responsibility. Survivor Olan Horne references his exasperation as he describes trying to dialogue with Cardinal Law: “How do you hold a man accountable for something he doesn’t think he’s done?”

Collectively these two bodies of work create a powerful dialogue and exponential impact. Kessler’s work looks out into collective public space, the world of activism, institutions, and politics, while Mandle’s work creates a safe, vulnerable respite, drawing the viewer back into self-reflection. Mandle’s quiet pilgrimage was singular and personal; seen with Kessler’s work, it brings forward the journeys of all survivors, each still having their own reconciliations, long after the news cameras have gone. Together, the two modes of observation offer a mechanism for transferring shame from wounded individuals to the structures that caused the harm.

Double Negative offers mobility for the traumatized psyche: while we can’t be liberated from trauma, we can strive for the insight to recognize it in its many disguises, and steer around it, or, to some extent, harness it to new uses. The work resonates with our nation today, as we reckon with historical inequalities of race, gender, class and environmental justice, reflecting on what we see, and creating systems of power rooted in transparency, vulnerability and accountability.